GOYA, FRANCISCO.

Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"]

Herman H. J. Lynge & Søn A/S

lyn60282

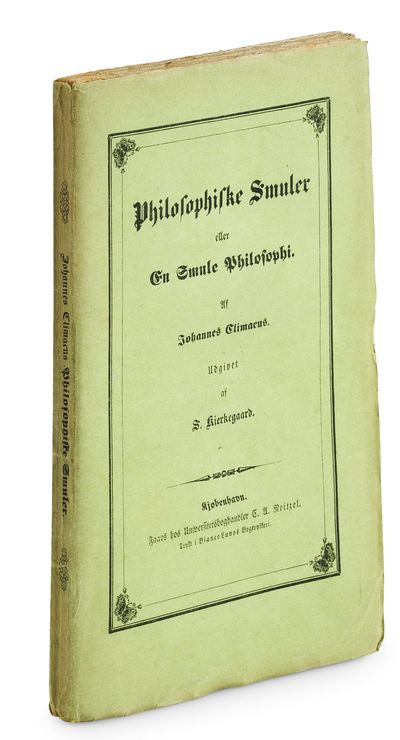

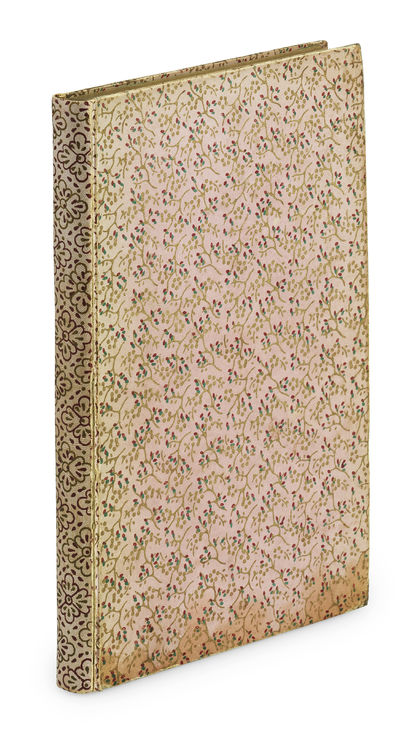

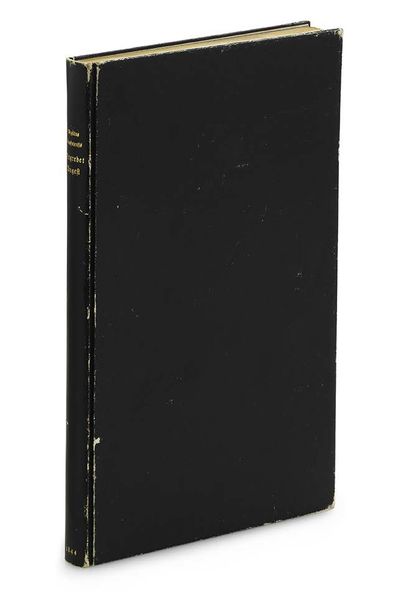

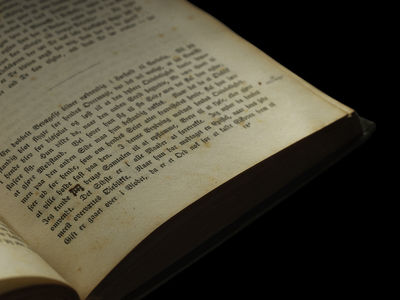

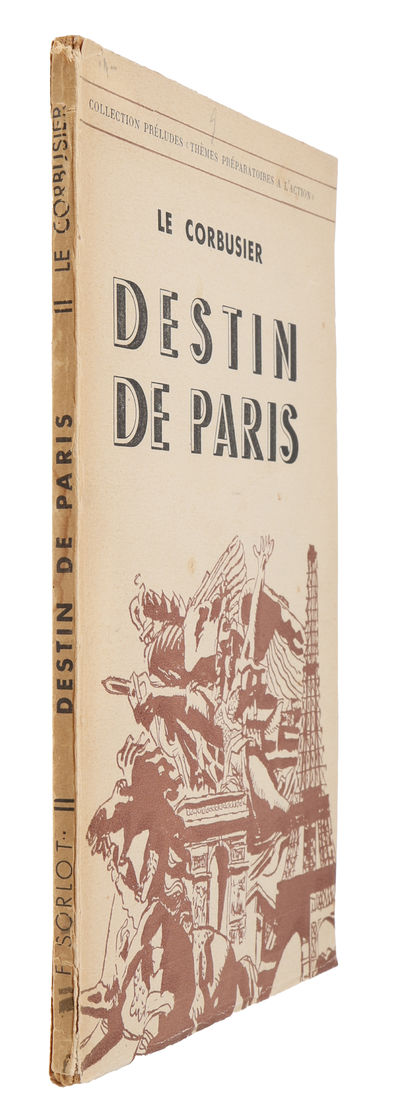

Madrid, 1906. Folio oblong. Bound in a splendid recent full longgrained burgundy morocco binding in pastiche style, with four raised bands to beautifully gilt spine. Boards with gilt ornamental borders and gilt centre-piece. Gilt line to edges of boards and inner gilt dentelles. Marbled end-papers. All leaves re-hinged. Occasional light brownspotting, but overall very nice. Title-page (the version with the second line (beginning "Colección de Ochenta...) in lower case), 2 pp. of text (dated 1863) + 80 engraved plates (on fine, laid paper measuring 23,4x32 cm.). Plates 17 and 77 have been misbound (the numbers 1 and 7 look almost the same - Harris II:201: "In some sets this plate has been bound out of order where the number hs been read as 77"; II:288: "In some sets this plate has been bound out of order where the number has been read as 17).

A beautiful copy of the splendid fourth edition of Goya's magnificent "Disasters of War" - one of the most significant anti-war works of art ever produced - consisting in all 80 plates that were issued. "The Disasters of War" constitutes Goya’s political masterpiece, directly inspired by and documenting the horrors he witnessed during the Peninsular War of 1808-14 between Spain and France under Napoleon Bonaparte, the terrible famine in Madrid in 1811-12, and the disappointment at the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. As such, it is one of the earliest and most important examples of war documentation and remains to this day one of the boldest anti-war statements ever made. This, however, is also the reason why these groundbreaking etchings were not published during Goya’s life-time. It was both too dangerous and too gruesome. As Alastair Sooke puts it, "[e]ven today it is difficult to look at the Disasters, because Goya catalogues the brutality and fatal consequences of war in such a stark, confrontational and unflinching manner." (See his article for BBC Culture, 2014). In this seminal series of etchings, Goya not only uses art to comment on politics and the atrocities connected with war, he also pioneers a number of artistic tools. Breaking from painterly traditions, he deviates from the heroics of most previous war art to show us how war can bring out the worst in humanity. He abandons colour in order to show us a more direct truth conveyed by the use of shadow and shade. Also, the fact that he presents the 80 works of art as a collection, together with the harsh, realistic nature of the etchings themselves, connect the images more closely to the art of photography that we are now so familiar with, causing the work as a whole to be viewed as one of the earliest examples of actual first-hand war reportage. The work has been extremely influential, perhaps most famously inspiring Pablo Picasso and Ernest Hemingway (For Whom the Bells Toll). "There are many contenders for the most powerful example of war art from the past two centuries: Picasso’s Guernica (1937), painted in response to the bombing of a Basque village during the Spanish Civil War, would be an obvious choice. For me, though, nothing quite matches the originality and truth-telling ferocity of the Disasters of War, a series of 80 aquatint etchings, complete with caustic captions, by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya (1746-1828)." (Sooke). The execution of the engravings has been dated to a period between 1810 and 1820, but no contemporary edition was made of this spectacular series. "Possibly by the time they were finished, the war and famine scenes were not of great appeal, and Goya was probably unwilling to risk another financial failure such as he had experienced with the "Caprichos". It was a time of stern repression and the publication of the satirican and violently anti-clerical subjects of some of the "caprichos enfánticos" would certainly have been dangerous. These facts would account for a postponement of publication. Also, Goya himself tells us that he fell seriously ill in the winter of 1819... and on his recovery he was planning to leave Spain and settle permanently in France. That Goya did not attempt to make an edition of "Desastres" in Madrid before leaving for France is borne out by the investigations of Catharina Boelcke-Astor, who showed that the copperplates were stored away in safes by Goya's son Javier, where they remained until the latter's death in 1854. Eventually, in November 1862, they were acquired by the Academia de San Fernando from D. Jaimé Machén for 28,000 reales..." (Harris I:141). In 1863, the first edition of Goya's seminal work was issued, under the famous title "Los desastres de la guerra". In all, 500 copies were issued. A second edition followed in 1892, and a third in 1903. Both of these editions were issued in merely 100 copies. In 1906, the fourth edition appeared, in a number of 275 copies. "This edition is excellently printed on very suitable papers" (Harris II: 175) and is considered much superior to the third. A further three editions appeared, in 1923, 1930, and 1937 respectively. "When Goya had engraved all the plates of the "Desastres" he gave his friend, Céan Bermúdez, an album containing a proof set of eighty-five plates, including the eighty plates eventually published as "Los Desastres de la Guerra", two plates numbered 81 and 82, which were prepared for the series but not published with it, and the three little engravings of "prisoners", which were never intended by Goya for inclusion in a published edition of the series." (Harris I:140). The first plate prepares the spectator for the contents of the series and can be seen as a sort of frontispiece, plates 2-47 deal mainly with the horrors of the war, plates 48-64 record the terrible famine in Madrid, and the final plates 65-80 constitute the "Caprichos enfánticos". " "The impact of the scenes is incredible," says the independent art historian Juliet Wilson-Bareau, one of the world’s leading Goya experts. "Each one is a powerful, original work of art in its own right, yet linked to the others with a common theme, including the way their titles - terse comments, questions, or cries of outrage - connect them, and read on from one to another. The grouping of the series into three ‘chapters’ gives the whole a sense of rhythm and purpose." Goya must have hoped that he would live to see the publication of his Disasters, but the despotic rule of Ferdinand VII made this impossible. "Under his repressive and reactionary regime," Wilson-Bareau explains, "there was no way that Goya could have published his set of prints that so clearly denounced all violence and all abuse of power." Still, following their posthumous publication, the Disasters proved enormously influential, inspiring artists including the German Otto Dix as well as Dalí and Picasso - and, more recently, the British brothers Jake and Dinos Chapman, who bought a complete edition of the prints and ‘defaced’ them by adding grotesque, cartoonish faces. Even the war photographer Don McCullin acknowledges a debt: "When I took pictures in war, I couldn’t help thinking of Goya," he has said. The genius of the Disasters is that they transcend particularities of the Peninsular War and its aftermath to feel universal - and modern. Perhaps this is because, as the British writer Aldous Huxley put it in 1947, "All [Goya] shows us is war’s disasters and squalors, without any of the glory or even picturesqueness." So should we consider the series as the greatest war art ever created? Wilson-Bareau certainly thinks so. "For me, yes," she tells me. "I have lived with these prints, which many people consider too shocking, absolutely unbearable, and I find in them - besides the heartbreak and outrage at the unspeakable violence and damage - a great well of compassion for all victims of the suffering and abuses they depict, which goes to the very heart of our humanity." (From Alastair Sooke's BBC-article). Harris II: 175.

A beautiful copy of the splendid fourth edition of Goya's magnificent "Disasters of War" - one of the most significant anti-war works of art ever produced - consisting in all 80 plates that were issued. "The Disasters of War" constitutes Goya’s political masterpiece, directly inspired by and documenting the horrors he witnessed during the Peninsular War of 1808-14 between Spain and France under Napoleon Bonaparte, the terrible famine in Madrid in 1811-12, and the disappointment at the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. As such, it is one of the earliest and most important examples of war documentation and remains to this day one of the boldest anti-war statements ever made. This, however, is also the reason why these groundbreaking etchings were not published during Goya’s life-time. It was both too dangerous and too gruesome. As Alastair Sooke puts it, "[e]ven today it is difficult to look at the Disasters, because Goya catalogues the brutality and fatal consequences of war in such a stark, confrontational and unflinching manner." (See his article for BBC Culture, 2014). In this seminal series of etchings, Goya not only uses art to comment on politics and the atrocities connected with war, he also pioneers a number of artistic tools. Breaking from painterly traditions, he deviates from the heroics of most previous war art to show us how war can bring out the worst in humanity. He abandons colour in order to show us a more direct truth conveyed by the use of shadow and shade. Also, the fact that he presents the 80 works of art as a collection, together with the harsh, realistic nature of the etchings themselves, connect the images more closely to the art of photography that we are now so familiar with, causing the work as a whole to be viewed as one of the earliest examples of actual first-hand war reportage. The work has been extremely influential, perhaps most famously inspiring Pablo Picasso and Ernest Hemingway (For Whom the Bells Toll). "There are many contenders for the most powerful example of war art from the past two centuries: Picasso’s Guernica (1937), painted in response to the bombing of a Basque village during the Spanish Civil War, would be an obvious choice. For me, though, nothing quite matches the originality and truth-telling ferocity of the Disasters of War, a series of 80 aquatint etchings, complete with caustic captions, by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya (1746-1828)." (Sooke). The execution of the engravings has been dated to a period between 1810 and 1820, but no contemporary edition was made of this spectacular series. "Possibly by the time they were finished, the war and famine scenes were not of great appeal, and Goya was probably unwilling to risk another financial failure such as he had experienced with the "Caprichos". It was a time of stern repression and the publication of the satirican and violently anti-clerical subjects of some of the "caprichos enfánticos" would certainly have been dangerous. These facts would account for a postponement of publication. Also, Goya himself tells us that he fell seriously ill in the winter of 1819... and on his recovery he was planning to leave Spain and settle permanently in France. That Goya did not attempt to make an edition of "Desastres" in Madrid before leaving for France is borne out by the investigations of Catharina Boelcke-Astor, who showed that the copperplates were stored away in safes by Goya's son Javier, where they remained until the latter's death in 1854. Eventually, in November 1862, they were acquired by the Academia de San Fernando from D. Jaimé Machén for 28,000 reales..." (Harris I:141). In 1863, the first edition of Goya's seminal work was issued, under the famous title "Los desastres de la guerra". In all, 500 copies were issued. A second edition followed in 1892, and a third in 1903. Both of these editions were issued in merely 100 copies. In 1906, the fourth edition appeared, in a number of 275 copies. "This edition is excellently printed on very suitable papers" (Harris II: 175) and is considered much superior to the third. A further three editions appeared, in 1923, 1930, and 1937 respectively. "When Goya had engraved all the plates of the "Desastres" he gave his friend, Céan Bermúdez, an album containing a proof set of eighty-five plates, including the eighty plates eventually published as "Los Desastres de la Guerra", two plates numbered 81 and 82, which were prepared for the series but not published with it, and the three little engravings of "prisoners", which were never intended by Goya for inclusion in a published edition of the series." (Harris I:140). The first plate prepares the spectator for the contents of the series and can be seen as a sort of frontispiece, plates 2-47 deal mainly with the horrors of the war, plates 48-64 record the terrible famine in Madrid, and the final plates 65-80 constitute the "Caprichos enfánticos". " "The impact of the scenes is incredible," says the independent art historian Juliet Wilson-Bareau, one of the world’s leading Goya experts. "Each one is a powerful, original work of art in its own right, yet linked to the others with a common theme, including the way their titles - terse comments, questions, or cries of outrage - connect them, and read on from one to another. The grouping of the series into three ‘chapters’ gives the whole a sense of rhythm and purpose." Goya must have hoped that he would live to see the publication of his Disasters, but the despotic rule of Ferdinand VII made this impossible. "Under his repressive and reactionary regime," Wilson-Bareau explains, "there was no way that Goya could have published his set of prints that so clearly denounced all violence and all abuse of power." Still, following their posthumous publication, the Disasters proved enormously influential, inspiring artists including the German Otto Dix as well as Dalí and Picasso - and, more recently, the British brothers Jake and Dinos Chapman, who bought a complete edition of the prints and ‘defaced’ them by adding grotesque, cartoonish faces. Even the war photographer Don McCullin acknowledges a debt: "When I took pictures in war, I couldn’t help thinking of Goya," he has said. The genius of the Disasters is that they transcend particularities of the Peninsular War and its aftermath to feel universal - and modern. Perhaps this is because, as the British writer Aldous Huxley put it in 1947, "All [Goya] shows us is war’s disasters and squalors, without any of the glory or even picturesqueness." So should we consider the series as the greatest war art ever created? Wilson-Bareau certainly thinks so. "For me, yes," she tells me. "I have lived with these prints, which many people consider too shocking, absolutely unbearable, and I find in them - besides the heartbreak and outrage at the unspeakable violence and damage - a great well of compassion for all victims of the suffering and abuses they depict, which goes to the very heart of our humanity." (From Alastair Sooke's BBC-article). Harris II: 175.

Adresse:

Silkegade 11

DK-1113 Copenhagen Denmark

Telefon:

CVR/VAT:

DK 16 89 50 16

E-post:

Nettsted:

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 1)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.0.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 2)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.1.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 3)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.2.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 4)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.3.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 5)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.4.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 6)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.5.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 7)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.6.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 8)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.7.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 9)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.8.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 10)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.9.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 11)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.10.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 12)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.11.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 13)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.12.l.0.jpg)

![Los desastres de la guerra. Colección de ochenta láminas inventadas y grabadas al agua-fuerte. Publicala la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. - ["THE MOST SEARING WORKS OF ART EVER TO DEAL WITH CONFLICT"] (photo 14)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/622/991/1527991622.13.l.0.jpg)