KIERKEGAARD, SØREN.

Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS]

Herman H. J. Lynge & Søn A/S

lyn62133

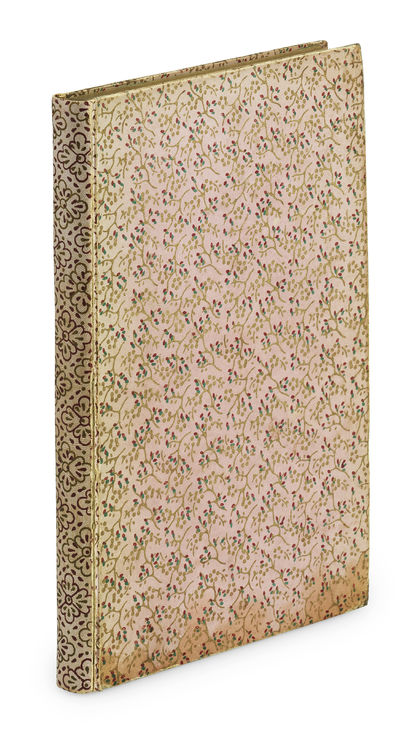

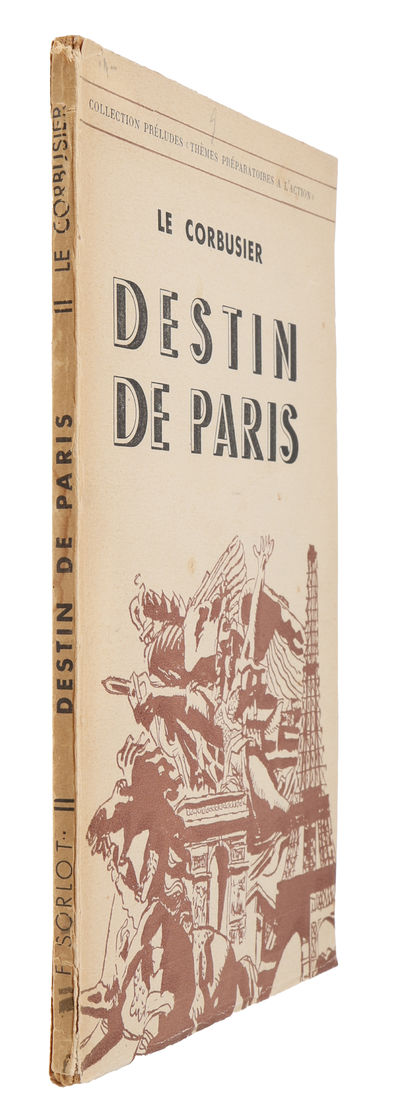

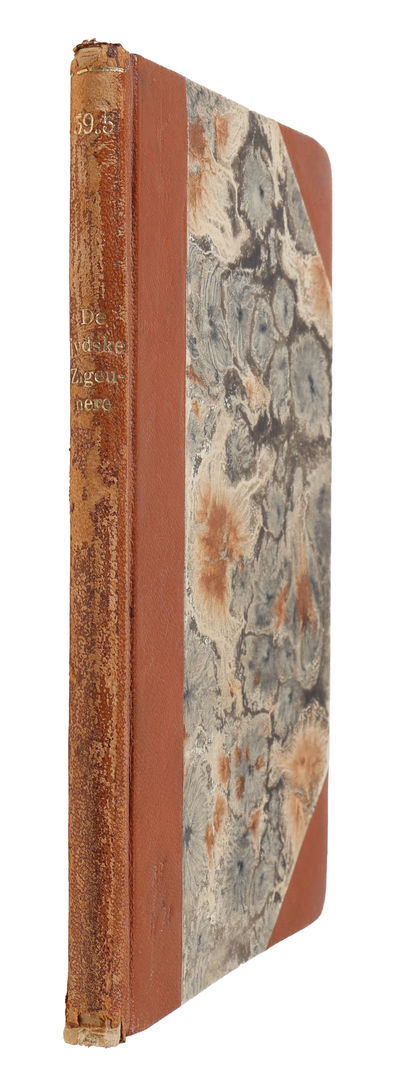

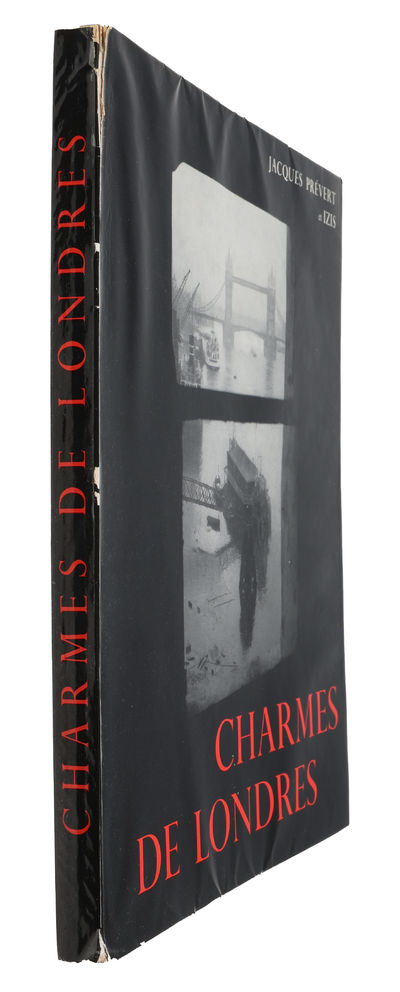

Kjøbenhavn, Reitzel, 1849. 8vo. XIV, (2), 320; (4), 250 pp. Bound in one original green full cloth binding with blindstamped decorative borders to boards and blindstamped lines and gilt title to spine. Rebacked preserving most of the original spine. White moiré end-papers and all edges gilt. Corners bumped. First title-page browned and brownspotting throughout. Previous owner’s neat pencil annotations about the history of the copy to back free end-paper and annotations/corrections in Kierkegaard’s hand to pp. 208 and 275 of vol. 1.

Kierkegaard’s own personal copy of the second issue of Either-Or, with his own corrections – one of them correcting a “not” to an “either”! This copy is with all likelihood nr. 2116 of the auction catalogue of Kierkgaard’s book collection – there merely described as “dainty binding with gilt edges”. The title-gilding on the spine, including the types, the fond, and the size, is identical to that of the five presentation-bindings of the second edition of Either-Or that have been preserved and identified (the ones for Hertz, Andersen, and Winther being the only ones with the presentation-inscription preserved). The spine- and the border-decoration, however, differs, as there is no decorative border on the other copies, which all have gilt volume-identification on them. This is clearly one of the dainty copies Kierkegaard had made, but differing somewhat from the copies he gave away. The style of the handwritten corrections is identical to those in Kierkegaard’s copy of Stadier paa Livets Vei (Stages on Life’s Way) (ex the collection of Muüllertz). The two corrections are:Vol. 1 p. 208: correcting “ret” to “vel”, i.e. meaning to change the sentence “One rightfully feels” to “One presumably feels”Vol. 1 p. 275: correcting “ikke” to “enten”, i.e. meaning to change the sentence “I could not use the conversation…” to “I could either use the conversation…” The two errors were first publicly identified with the publication of Kierkegaard’s collected works half a century later. It is absolutely magnificent to have here what is with all likelihood Kierkegaard’s own personal copy of his magnum opus, with his own handwritten corrections in it. In the light of the history of the work, it makes perfect sense for Kierkegaard to have used and read the second edition of the work. Kierkegaard’s magnum opus Either-Or is considered the foundational work of existentialism and doubtlessly the most famous work by the greatest Scandinavian philosopher of all times, who "is now generally considered to be, however eccentric, one of the most important Christian philosophers" (PMM 314). Kierkegaard's monumental magnum opus seminally influenced later as well as contemporary philosophy and ranks as one of the most important works of philosophy of modern times. Either-Or is the earliest of Kierkegaard’s major works and the work with which he begins his pseudonymous authorship. Kierkegaard’s pseudonymity is an entire subject unto its own. The various cover names he uses play a significant role in his way of communicating and are essential to the understanding of his philosophical and religious messages. And it all properly begins here, with his groundbreaking magnum opus. Conjuring up two distinctive figures with diverging beliefs and modes of life – the aesthetic “A” of Part One, and the ethical B (note that this is the first “pseudonym” that Kierkegaard uses, in his earliest articles – no. I above)/Judge Vilhelm of Part Two, Kierkegaard presents us with the most basic reflections on the search for a meaningful existence, seen from two completely different philosophical views. This masterpiece of duality explores the foundational conflict between the ethical and the aesthetical, providing us along the way with the now so famous contemplations on music (Mozart), drama, boredom, pleasures, virtues, and, probably most famously, seduction (and rejection – The Seducer’s Diary). It is primarily Judge Vilhelm from Part Two of Either-Or that has bestowed upon Kierkegaard the reputation as the Father of Existentialism. His emphasis on taking ownership of oneself and the importance of making choices has made him the (first) personification of Existentialism and the idea that one does not passively develop into the self that he or she should be or ought to become. Kierkegaard went to great lengths to ensure that the public would not know the identity of the author was of Either-Or. He even had the draft of the work done by several hands, so that employees at the printer’s would also be deceived. Despite his efforts, however, it did not take long for the public to guess that Kierkegaard had written this astounding work. But Kierkegaard himself kept up the façade and did not accept authorship until several years later. Nothing Kierkegaard did was left to chance, which his carefully chosen pseudonyms also reflect. This also spills over in his presentation-inscriptions, which follow as strict a pattern as the pseudonyms themselves – he never signed himself the author, if his Christian name was not listed as the author on the title-page. And seeing that he had not accepted authorship of Either-Or and is not mentioned by name anywhere on the title-page (also not as the editor nor publisher as with the other pseudonymous works), he was not able to give away copies of his magnum opus, which is why no presentation-copy of the first edition exists. The appearance of the second edition of this monumental work was, naturally, carefully planned. Either-Or first appeared in 1843, and due to the great demand for the work, which had originally only been printed in ca 525 copies, it had quickly been sold out; but Kierkegaard refused to have it reprinted. In 1849, finally, he decided to let it appear again, in a textually unchanged version. When the second edition appeared (recte second issue), Kierkegaard had meanwhile owned up to the authorship of Either-Or. He had done so in 1846, in his Concluding Unscientific Postscript to The Philosophical Fragments (own translation): “For the sake of manners and etiquette I hereby acknowledge, what can hardly in reality be of interest to anybody to know, that I am, as one says, the author of Either-Or (Victor Eremita), Copenhagen in February 1843...”. Now, finally, Kierkegaard could give away his magnum opus! In his Papers from 1849, Kierkegaard states (own translation): “The poets here at home each received a copy of Either-Or. I thought it my duty; and now I was able to do it; because now one cannot reasonably claim that a conspiracy is made concerning the book. -because the book is now old and its crisis over. Of course they were given the copy from Victor Eremita...” (Pap., X1A 402). Naturally, because “as little as I in Either-Or is the Seductor or the Assessor, as little am I the publisher Victor Eremita, exactly as little; he is a poetically-real subjective thinker, as he is also found in “in vino veritas.” “ (the postscript to the Postscript, 1846) But he only sent few copies to very choice people, fewer than he did most of his other works, and only three copies have been identified (to Henrik Hertz, Christian Winther, and Hans Christian Andersen). Three further copies in gift-bindings corresponding to these have been identified, but in these copies, the leaf with the presentation-inscription has also been torn out. He must have given away yet another copy – one presumably not being on vellum-paper, as, according to his own notes, he had asked the printers for six copies on vellum paper (see Pap., Vol. X, part five, p. (203).) -, making the total known (albeit not all identified) number of copies seven. “Two copies in a binding corresponding to Hertz’s copy have been traced, but in both, the front free end-paper has been torn out. It leads one to think that the completely unusual presentation inscription (signed by Victor Eremita!), for the immediate posterity has been of such a curious nature that it has tempted autograph hunters on several occasions.” (Tekstspejle, p. 97, translated from Danish). “The other book, of which the recipients stand out is the second edition of Either-Or, which appeared in May 1849. The first edition from 1843 had been sold out for several years, but Kierkegaard had refused to have it reprinted. In our context we must remember that in 1843, he was unable to send gift copies of the first edition… When, in 1843, he lets Either-Or be reprinted in textually unaltered form, he has meanwhile (1846) admitted to authorship of the work. But the wording on the title-pages of the two leaves does not allow him to sign the dedication “from the Author” or “from the publisher” or the like.” (Tekstspejle p. 96, translated from Danish). Either-Or is now not only the title of Kierkegaard’s most famous and widely read work, it is also a phrase that summarizes much of the thinking for which he is best known and a cornerstone of what we now characterize as Existentialism. The first edition caused a sensation. The second issue (termed “edition”, although it is textually unaltered) is not only the first edition of the work to appear after Kierkegaard had acknowledged authorship of it and thus also confirmed being one and the same with his most famous pseudonym, it is also the first of Kierkegaard’s works to appear in a second edition or issue. The second edition of the work is thus also of the utmost importance and is one of the only important second editions of any of Kierkegaard’s works. Only a few months after Kierkegaard died (11th of November 1855), at the beginning of April 1856, his books were put up for sale. The sale was an event which created stir among scholars all over Denmark, and the event drew large crowds. Everyone wanted a piece of the recently deceased legend, and bidding was lively. The average price for the single items was nearly a rix-dollar a very high price for that time. As the old Herman Lynge wrote in a letter on the 22nd of May (The Royal Library, Recent Letters, D.), to the famous collector F.S. Bang, “At the sale of Dr. Søren Kierkegaard’s books everything went at very high prices, especially his own works, which brought 2 or 3 times the published prices”.” (Rohde Auction Catalogue, p. LVIJ). Many authors, philosophers, and scholars were present in the auction room, which was completely full, as was the Royal Library, who bought ca 80 lots. “Many of the books, not only his own, were paid for with much higher prices than in the book shops” (In Morgenposten no. 99, 30. April 1856, written by “P.”, translated from Danish). "Some books were bought by libraries where they still are today, others were bought by private people, who sometimes wrote their names in the front of the books and thus, indirectly, stated that they came from Kierkegaard’s book collection… The edition (of the auction catalogue, 1967) registers all books from Kierkegaard’s book collection that it has hitherto been possible to identify – either in public or in private ownership… All in all, nearly a couple of hundred volumes – i.e. ca. 10 % – of the Kierkegaardian book collection is said to be rediscovered…" (Rohde). Thus, today, books from Kierkegaard’s library are of the utmost scarcity. Only very few are still possible to acquire, and they hardly ever appear on the market. PMM: 314 Himmelstrup 21

Kierkegaard’s own personal copy of the second issue of Either-Or, with his own corrections – one of them correcting a “not” to an “either”! This copy is with all likelihood nr. 2116 of the auction catalogue of Kierkgaard’s book collection – there merely described as “dainty binding with gilt edges”. The title-gilding on the spine, including the types, the fond, and the size, is identical to that of the five presentation-bindings of the second edition of Either-Or that have been preserved and identified (the ones for Hertz, Andersen, and Winther being the only ones with the presentation-inscription preserved). The spine- and the border-decoration, however, differs, as there is no decorative border on the other copies, which all have gilt volume-identification on them. This is clearly one of the dainty copies Kierkegaard had made, but differing somewhat from the copies he gave away. The style of the handwritten corrections is identical to those in Kierkegaard’s copy of Stadier paa Livets Vei (Stages on Life’s Way) (ex the collection of Muüllertz). The two corrections are:Vol. 1 p. 208: correcting “ret” to “vel”, i.e. meaning to change the sentence “One rightfully feels” to “One presumably feels”Vol. 1 p. 275: correcting “ikke” to “enten”, i.e. meaning to change the sentence “I could not use the conversation…” to “I could either use the conversation…” The two errors were first publicly identified with the publication of Kierkegaard’s collected works half a century later. It is absolutely magnificent to have here what is with all likelihood Kierkegaard’s own personal copy of his magnum opus, with his own handwritten corrections in it. In the light of the history of the work, it makes perfect sense for Kierkegaard to have used and read the second edition of the work. Kierkegaard’s magnum opus Either-Or is considered the foundational work of existentialism and doubtlessly the most famous work by the greatest Scandinavian philosopher of all times, who "is now generally considered to be, however eccentric, one of the most important Christian philosophers" (PMM 314). Kierkegaard's monumental magnum opus seminally influenced later as well as contemporary philosophy and ranks as one of the most important works of philosophy of modern times. Either-Or is the earliest of Kierkegaard’s major works and the work with which he begins his pseudonymous authorship. Kierkegaard’s pseudonymity is an entire subject unto its own. The various cover names he uses play a significant role in his way of communicating and are essential to the understanding of his philosophical and religious messages. And it all properly begins here, with his groundbreaking magnum opus. Conjuring up two distinctive figures with diverging beliefs and modes of life – the aesthetic “A” of Part One, and the ethical B (note that this is the first “pseudonym” that Kierkegaard uses, in his earliest articles – no. I above)/Judge Vilhelm of Part Two, Kierkegaard presents us with the most basic reflections on the search for a meaningful existence, seen from two completely different philosophical views. This masterpiece of duality explores the foundational conflict between the ethical and the aesthetical, providing us along the way with the now so famous contemplations on music (Mozart), drama, boredom, pleasures, virtues, and, probably most famously, seduction (and rejection – The Seducer’s Diary). It is primarily Judge Vilhelm from Part Two of Either-Or that has bestowed upon Kierkegaard the reputation as the Father of Existentialism. His emphasis on taking ownership of oneself and the importance of making choices has made him the (first) personification of Existentialism and the idea that one does not passively develop into the self that he or she should be or ought to become. Kierkegaard went to great lengths to ensure that the public would not know the identity of the author was of Either-Or. He even had the draft of the work done by several hands, so that employees at the printer’s would also be deceived. Despite his efforts, however, it did not take long for the public to guess that Kierkegaard had written this astounding work. But Kierkegaard himself kept up the façade and did not accept authorship until several years later. Nothing Kierkegaard did was left to chance, which his carefully chosen pseudonyms also reflect. This also spills over in his presentation-inscriptions, which follow as strict a pattern as the pseudonyms themselves – he never signed himself the author, if his Christian name was not listed as the author on the title-page. And seeing that he had not accepted authorship of Either-Or and is not mentioned by name anywhere on the title-page (also not as the editor nor publisher as with the other pseudonymous works), he was not able to give away copies of his magnum opus, which is why no presentation-copy of the first edition exists. The appearance of the second edition of this monumental work was, naturally, carefully planned. Either-Or first appeared in 1843, and due to the great demand for the work, which had originally only been printed in ca 525 copies, it had quickly been sold out; but Kierkegaard refused to have it reprinted. In 1849, finally, he decided to let it appear again, in a textually unchanged version. When the second edition appeared (recte second issue), Kierkegaard had meanwhile owned up to the authorship of Either-Or. He had done so in 1846, in his Concluding Unscientific Postscript to The Philosophical Fragments (own translation): “For the sake of manners and etiquette I hereby acknowledge, what can hardly in reality be of interest to anybody to know, that I am, as one says, the author of Either-Or (Victor Eremita), Copenhagen in February 1843...”. Now, finally, Kierkegaard could give away his magnum opus! In his Papers from 1849, Kierkegaard states (own translation): “The poets here at home each received a copy of Either-Or. I thought it my duty; and now I was able to do it; because now one cannot reasonably claim that a conspiracy is made concerning the book. -because the book is now old and its crisis over. Of course they were given the copy from Victor Eremita...” (Pap., X1A 402). Naturally, because “as little as I in Either-Or is the Seductor or the Assessor, as little am I the publisher Victor Eremita, exactly as little; he is a poetically-real subjective thinker, as he is also found in “in vino veritas.” “ (the postscript to the Postscript, 1846) But he only sent few copies to very choice people, fewer than he did most of his other works, and only three copies have been identified (to Henrik Hertz, Christian Winther, and Hans Christian Andersen). Three further copies in gift-bindings corresponding to these have been identified, but in these copies, the leaf with the presentation-inscription has also been torn out. He must have given away yet another copy – one presumably not being on vellum-paper, as, according to his own notes, he had asked the printers for six copies on vellum paper (see Pap., Vol. X, part five, p. (203).) -, making the total known (albeit not all identified) number of copies seven. “Two copies in a binding corresponding to Hertz’s copy have been traced, but in both, the front free end-paper has been torn out. It leads one to think that the completely unusual presentation inscription (signed by Victor Eremita!), for the immediate posterity has been of such a curious nature that it has tempted autograph hunters on several occasions.” (Tekstspejle, p. 97, translated from Danish). “The other book, of which the recipients stand out is the second edition of Either-Or, which appeared in May 1849. The first edition from 1843 had been sold out for several years, but Kierkegaard had refused to have it reprinted. In our context we must remember that in 1843, he was unable to send gift copies of the first edition… When, in 1843, he lets Either-Or be reprinted in textually unaltered form, he has meanwhile (1846) admitted to authorship of the work. But the wording on the title-pages of the two leaves does not allow him to sign the dedication “from the Author” or “from the publisher” or the like.” (Tekstspejle p. 96, translated from Danish). Either-Or is now not only the title of Kierkegaard’s most famous and widely read work, it is also a phrase that summarizes much of the thinking for which he is best known and a cornerstone of what we now characterize as Existentialism. The first edition caused a sensation. The second issue (termed “edition”, although it is textually unaltered) is not only the first edition of the work to appear after Kierkegaard had acknowledged authorship of it and thus also confirmed being one and the same with his most famous pseudonym, it is also the first of Kierkegaard’s works to appear in a second edition or issue. The second edition of the work is thus also of the utmost importance and is one of the only important second editions of any of Kierkegaard’s works. Only a few months after Kierkegaard died (11th of November 1855), at the beginning of April 1856, his books were put up for sale. The sale was an event which created stir among scholars all over Denmark, and the event drew large crowds. Everyone wanted a piece of the recently deceased legend, and bidding was lively. The average price for the single items was nearly a rix-dollar a very high price for that time. As the old Herman Lynge wrote in a letter on the 22nd of May (The Royal Library, Recent Letters, D.), to the famous collector F.S. Bang, “At the sale of Dr. Søren Kierkegaard’s books everything went at very high prices, especially his own works, which brought 2 or 3 times the published prices”.” (Rohde Auction Catalogue, p. LVIJ). Many authors, philosophers, and scholars were present in the auction room, which was completely full, as was the Royal Library, who bought ca 80 lots. “Many of the books, not only his own, were paid for with much higher prices than in the book shops” (In Morgenposten no. 99, 30. April 1856, written by “P.”, translated from Danish). "Some books were bought by libraries where they still are today, others were bought by private people, who sometimes wrote their names in the front of the books and thus, indirectly, stated that they came from Kierkegaard’s book collection… The edition (of the auction catalogue, 1967) registers all books from Kierkegaard’s book collection that it has hitherto been possible to identify – either in public or in private ownership… All in all, nearly a couple of hundred volumes – i.e. ca. 10 % – of the Kierkegaardian book collection is said to be rediscovered…" (Rohde). Thus, today, books from Kierkegaard’s library are of the utmost scarcity. Only very few are still possible to acquire, and they hardly ever appear on the market. PMM: 314 Himmelstrup 21

Address:

Silkegade 11

DK-1113 Copenhagen Denmark

Phone:

CVR/VAT:

DK 16 89 50 16

Email:

Web:

![Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS] (photo 1)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/641/685/1714685641.0.l.jpg)

![Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS] (photo 2)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/641/685/1714685641.1.l.jpg)

![Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS] (photo 3)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/641/685/1714685641.2.l.jpg)

![Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS] (photo 4)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/641/685/1714685641.3.l.jpg)

![Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS] (photo 5)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/641/685/1714685641.4.l.jpg)

![Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS] (photo 6)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/641/685/1714685641.5.l.jpg)

![Enten – Eller. Et Livs=Fragment udgivet af Victor Eremita. Anden Udgave. Første Deel, indeholdende A.’s Papirer + Anden Deel, indeholdende B.’s Papirer, Breve til A. - [KIERKEGAARD’S OWN PERSONAL COPY OF EITHER-OR, WITH HIS OWN CORRECTIONS] (photo 7)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/641/685/1714685641.6.l.jpg)